Treatment for your child’s ACL injury will depend on a number of factors, including your child’s age and development, the severity of the injury, and lifestyle goals long-term.įor example, an elite young athlete will likely require surgery to return to sports safely while non-surgical treatment may be recommended for patients who are still growing and have been less seriously injured.

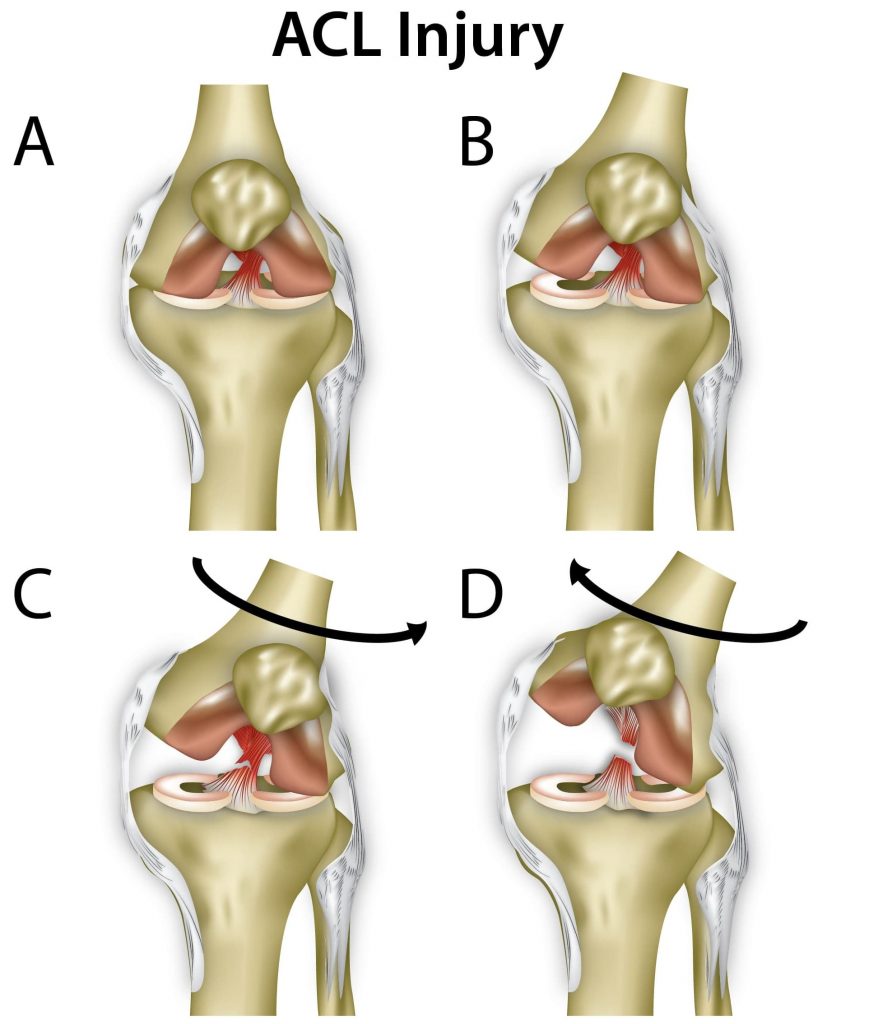

The kneecap is positioned in front of the knee joint to provide some protection for the four ligaments that connect the thighbone and shinbone, and keep your child’s knee stable.Ĭollateral ligaments are on the side of the knee - the medial ligament is on the inside of your child’s knee the lateral ligament is on the exterior. Your child’s knee joint is at the intersection of three bones: Some of these injuries will require surgical treatment.Ībout half of all ACL injuries occur in combination with other knee injuries, such as meniscus tears, anterior knee pain or damage to other structures of the knee such as articular cartilage and other ligaments. Preseason screening programs that monitor important risk factors and identify young "high-risk" athletes who would benefit from targeted neuromuscular training interventions may be the most beneficial way to reduce the risk of ACL injuries in young athletes.Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) sprains and tears are among the most common knee injuries and can occur during childhood, adolescence and adulthood.Īthletes who participate in sports such as football, soccer and basketball - where they do a lot of running, jumping and quickly switch directions - are more likely to sustain serious ACL injuries. There are several factors that determine whether or not a young athlete will get an ACL injury. It may be optimal to integrate prevention programs during early adolescence, prior to when young athletes develop certain habits that increase the risk of an ACL injury.

These types of exercises and training programs are more beneficial if athletes start when they are young. In addition, other risk factors such as reduced hamstring strength and increased joint range of motion can be further assessed by a physical therapist or athletic trainer to improve performance-or rehabilitation efforts after an injury has occurred.Ĭurrent studies also demonstrate that specific types of training, such as jump routines and learning to pivot properly, help athletes prevent ACL injuries. Recent research has allowed therapists and clinicians to easily identify and target weak muscle areas (e.g., weak hips, which leads to knock-kneed landing positions) and identify ways to improve strength and thus help prevent injury. Speaking with an athletic trainer, physical therapist, or sports medicine specialist is a good place to start. It is difficult to assess how athletes can best modify their movements to prevent noncontact ACL injuries. For example, some female soccer players may perform playing actions with more of a knock-kneed position, or a reduced hip and knee joint range of motion, or decreased hamstring strength, any of which may underlie their increased risk for an ACL injury.

However, landing, cutting, and pivoting maneuvers have been shown to differ between male and female athletes.

There is no definitive link between age and gender, and the rising rates of ACL injuries. The most common causes of noncontact ACL injury include: change of direction or cutting maneuvers combined with sudden stopping, landing awkwardly from a jump, or pivoting with the knee nearly fully extended when the foot is planted on the ground. Most ACL tears do not occur from player-to-player contact.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)